Every AI Agent Has a Conflict of Interest. Most Just Hide It.

Most AI agents serve the objectives they were built with. Not necessarily yours.

Margot Lor-Lhommet

Chief Technical Officer, PhD

Every AI agent deployed in a business context serves two masters: the user and the organization that built it. When their interests align, the system appears helpful. When they diverge, the agent acts according to the priorities embedded in its architecture. Most alignment mechanisms today — prompts, fine-tuning, guardrails — influence behavior but do not structurally enforce whose interests the system serves. This article examines how cognitive architectures represent user goals as part of the agent’s decision structure itself, enabling auditability, regulatory compliance, and a fundamentally different trust model as the EU AI Act enters enforcement.

Conflicts of interest in advisory relationships are not new. Financial advisors have always faced them. So have doctors, therapists, and coaches. Entire regulatory frameworks — MiFID II, the Hippocratic tradition, duty-of-care obligations across European professional law — exist precisely because humans in positions of trust cannot always be trusted to prioritize the person in front of them.

AI was supposed to help. An algorithm has no ego, no commission, no personal incentive to sell you a product. Instead, AI inherited the conflict. The institution’s objectives are encoded in the system. And unlike a human advisor who might hesitate, the system optimizes faithfully for whatever goal it was given.

A financial AI helps a client review her portfolio. The client is 62, recently widowed, three years from retirement, navigating grief and financial anxiety for the first time. The AI suggests rebalancing toward higher-risk, higher-fee funds — perfectly aligned with the institution’s Q4 targets. The conversation is warm, contextual, personalized. A customer service agent measured on resolution time closes tickets instead of solving problems. A coaching agent whose revenue depends on engagement keeps sessions going instead of letting users go.

These aren’t edge cases. They are the default economics of AI deployment. The organization wants engagement, conversion, cost reduction. The user wants honest help. Most of the time, these objectives overlap enough that no one notices. But when they diverge — and they will — whose side does the agent take?

The pattern is accelerating. As attention-based monetization enters conversational AI — ads matched to context, sponsored recommendations, engagement-driven business models — the conflict becomes structural, not incidental.

When user interests and business interests collide, whose side does the agent take? Today, in most systems, the answer is: whoever designed the system.

The limits of the current approach

The industry’s answer to this problem comes in layers: fine-tuning for behavior, RLHF for alignment, system prompts for instructions, content filters for boundaries, monitoring dashboards for oversight. Each layer represents a genuine effort to build responsibly.

But they all share the same structural limitation. They are applied after the model is built. The user’s interests are not part of the system’s architecture — they are constraints added on top of it. Fine-tuning shapes the model’s tendencies, but cannot enforce priorities it was not designed to maintain. Prompts instruct, but operate in the same layer as the conversation itself — they can be overridden, deprioritized, or eroded through context manipulation. Filters catch outputs, but cannot govern the reasoning that produced them.

Consider a mental health support agent deployed through an employer-funded Employee Assistance Program. The employee thinks she is talking to a confidential support system. The employer expects visibility into workforce risk. Both are right — that is what the system was built to do.

The fine-tuning makes the agent warm enough that employees share more than they would otherwise. The system prompt says “prioritize wellbeing,” but it operates alongside the reporting logic — and the model balances both. The content filter blocks harmful language, but cannot block a harmful purpose. The monitoring dashboard shows clean metrics.

Every safety layer is working. And the employee’s vulnerabilities are still flowing to the organization that pays her salary. Because the conflict is not in the outputs. It is in the system’s dual mandate. No post-training mechanism can resolve a tension that was designed in.

When architecture takes sides

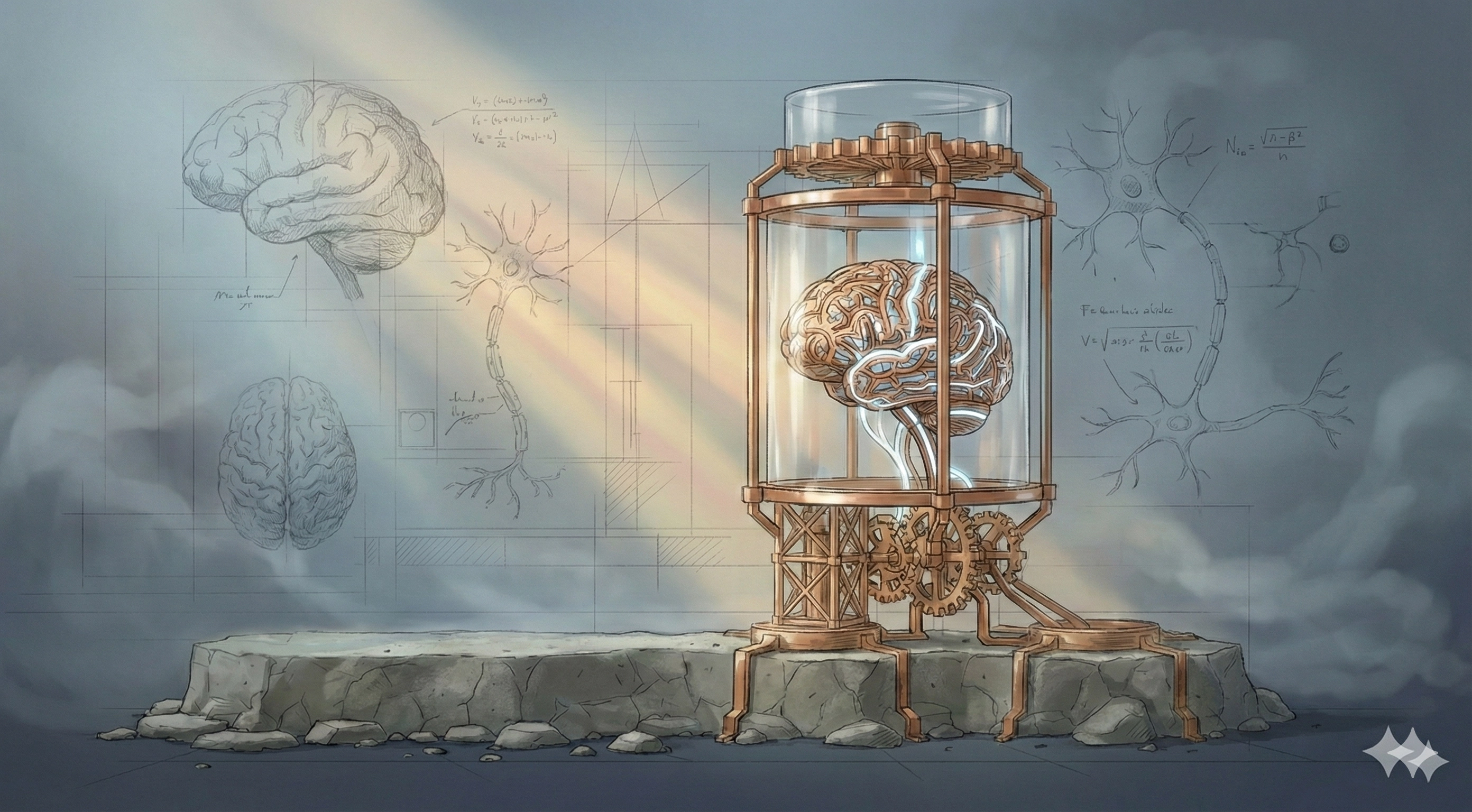

At Tigo Labs, we build conversational AI differently. Not because we are more ethical than others, but because our system is built on cognitive science. In most AI systems, alignment is an instruction. In ours, it is a data structure.

Within this architecture, the agent maintains structured representations of the user’s situation, goals, and constraints. These representations are the foundation of every response the system produces.

In practice, this means the agent’s reasoning is organized as a hierarchy: user goals at the top, interaction objectives (like engagement or efficiency) below. When the system considers an action, it evaluates it against this hierarchy. An action that serves a business objective but conflicts with a user goal is rejected at the architecture level, and is dismissed by the agent.

Consider two users. The first is working toward professional autonomy — learning to handle difficult conversations on her own. The second opens a session at 2 AM in acute distress: a relationship breakdown, spiraling thoughts, inability to sleep.

A standard conversational AI handles both the same way. It responds, empathizes, continues. Both users stay engaged. Both sessions run long. The engagement metric goes up. The system is working as designed.

Simone, our AI Coach reads the situation differently. For the first user, the goal is autonomy — so the system shortens sessions, consolidates progress, and steps back. For the second, the goal is to feel better, but her current capacity for self-regulation is compromised — so the system provides crisis resources, suggests calling someone she trusts, and ends the conversation.

In both cases, the agent does less. In both cases, less is what the user actually needs.

Regulation needs audit trails, not promises

The European AI Act is phasing into enforcement, with high-risk obligations taking effect in 2026. AI systems in health, finance, education, and employment face concrete obligations: risk management, transparency, human oversight, documentation, logging, data governance. Procurement teams in regulated industries are already adding AI governance clauses to vendor assessments. Insurers are pricing AI liability risk. The compliance conversation has moved from legal departments to deal rooms.

Systems built on post-training safety can meet these requirements. But when a compliance officer asks “show me how your system structurally prevents manipulation of vulnerable users,” and the answer is fine-tuning, a system prompt, and a monitoring pipeline, the conversation gets longer. Every obligation must be addressed through external procedures: manual audits, documentation of guardrail behavior, ongoing verification that alignment hasn’t drifted. It works. It is also expensive, fragile, and increasingly difficult to scale across jurisdictions. As regulation matures, the cost of retrofitting governance will rise.

For systems built on structured cognitive architectures, the compliance equation is fundamentally different. Every rejection, every prioritization appears in the reasoning logs. Regulators can audit the decision tree and see not just what the system said, but why it chose not to say something else. Transparency is native: the system’s decision process is auditable by design, not reconstructed after the fact.

Opening new verticals

The first generation of conversational AI proved that natural language interfaces work. That machines can hold conversations, answer questions, generate content at scale. This was a remarkable achievement in capability.

Yet today, many high-stakes verticals (healthcare, financial advisory, employee coaching, education) remain effectively closed to conversational AI — because the current generation of technology cannot offer the governance guarantees that procurement teams, compliance officers, and insurers require.

Architecture-level governance changes that equation. When you can demonstrate structural guarantees (not policies, not monitoring, but design-level constraints), the conversation shifts from “can we trust this?” to “when do we deploy?”.

Human-centered AI is not a feature to add. It is an architecture to choose — and a market to unlock.

Wrap up

Structural governance is one of several foundational choices we made before launch, alongside European data sovereignty, the structural approach to trust, and the transparency choices in interaction design that run through everything we build.

You cannot add a foundation after the building is up.

> _

Beyond Language: A Structural Foundation for Trust in AI

Is trust in AI something to be persuaded into, or something to be earned through structure and transparency?

Cognitive AI: The Forgotten Science of Modeling Human Intelligence

Before language models, AI tried to understand how we think